Long Meadow Road (formerly Long Swamp Road) courses through the property and has been repeatedly expanded and re-routed through time. While this has severely disrupted or covered some of the mining community structures as plotted on historic maps, traces of others survive. A Phase II intensive survey of most of the areas slated for development, however, revealed highly disturbed contexts which disqualify them from further conservation efforts. Artifact remains in one section of a residential site area revealed an extraordinary density and breadth of materials reflecting a 19th Century household setting, including ceramic wares, bottle and vessel glass, structural items, silverware, and personal items such as a pocket- watch casing and kaolin clay pipe stems. A "pepperbox" revolver was found down the road from the site, and represents a relatively rare armament which was first patented in 1837.

The Sterling Iron Mine Company was the last entity to mine iron ore on the property in 1917 towards the end of World War I. With the quality of the ore being less than ideal, there is a historic pattern of resurging mining activity in the area during times of war when more metal was required for the production of vehicles, weapons, and ammunition. Whole corporate communities were formed and integrated with the business and the landscape to the degree that the mining community represents an important and distinctive cultural entity. The severe degree of disturbance to the majority of historic sites along the road, however, prevents this area from being registered as a national archaeological district.

Documenting Inter-Site Functional and Chronological Variability: Troutbrook Valley

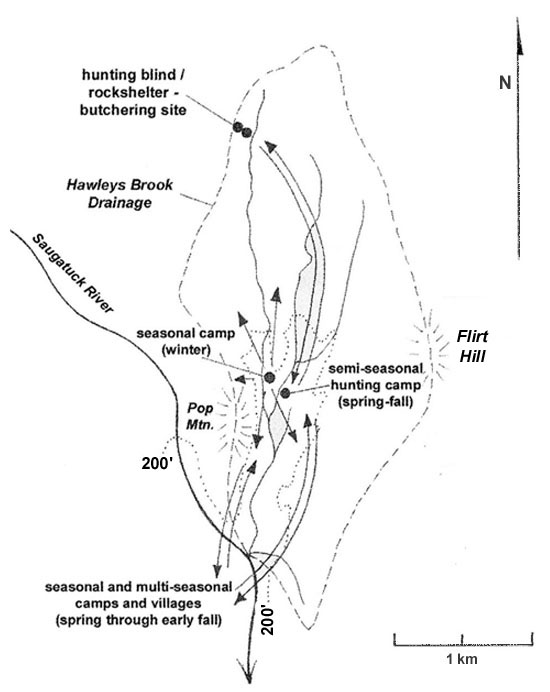

ACS performed a Phase II intensive archaeological survey on two of five prehistoric sites recorded during a Phase I reconnaissance survey of the Troutbrook Valley property in western Connecticut. The two sites were recorded in the heart of the core area exhibiting a high score as determined by a statistical prehistoric landscape sensitivity model created and employed by ACS. These sites were subjected to Phase II testing in order to evaluate their integrity, stratigraphic setting, areal extent, chronological setting, and functional nature.

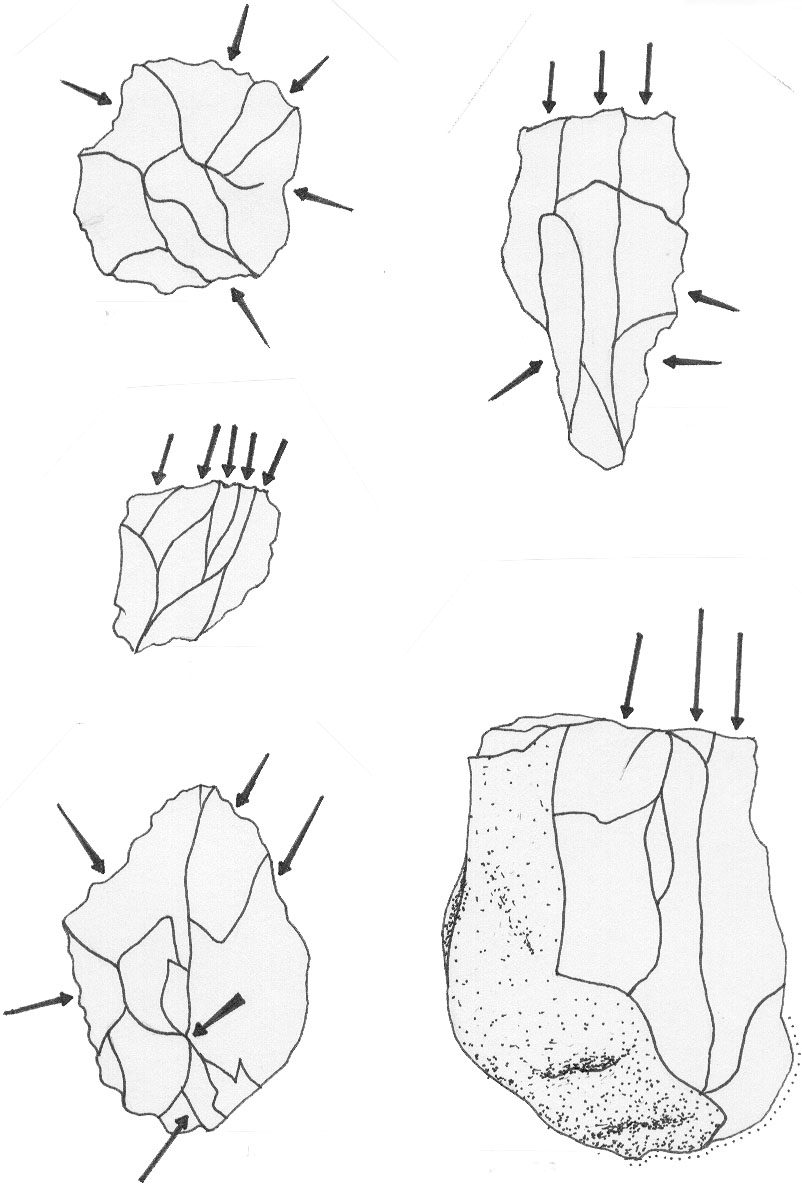

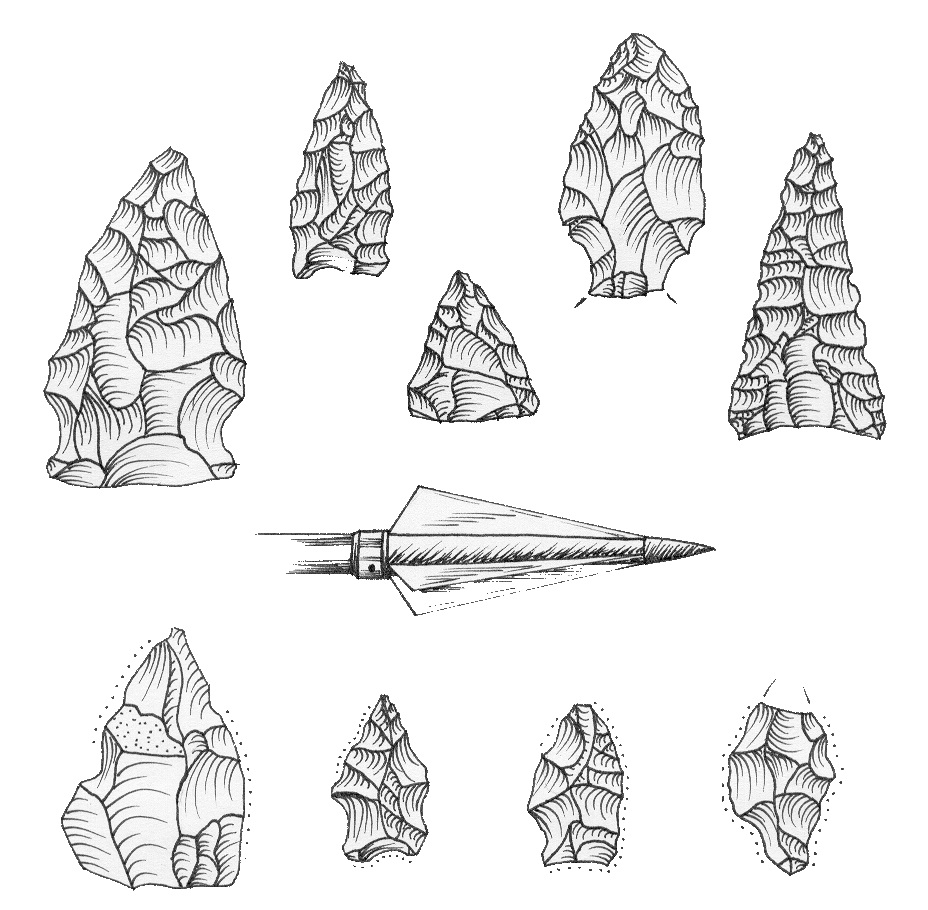

Materials from one site included a Lamoka projectile point and a knife close in form to a Brewerton eared point. Charcoal from a hearth or roasting pit feature exposed in one of the excavation units generated a radiocarbon date of 2,800+60 years ago indicating an occupation of the site towards the end of the Terminal Archaic period. A different portion of the same site contained an abundance of quartz cores and core fragments, as well as other debitage related to the initial procurement and reduction of cobbles from a nearby stream. The cores display a variety of reduction strategies likely related to variability encountered within this material type which was quite difficult to work. Lesser amounts of chert at the site represent the middle to end of the lithic reduction stream, suggesting that as an exotic material, chert was imported to the region in partly finished form (i.e. blanks and preforms).

The other site in this area contains a variability of projectile point forms spanning a time range from the Early or Middle Archaic to the Middle or Late Woodland period (minimally 6,000 to 2,000 years ago), including Stanly bifurcate, Sylvan side-notched, cf. Orient Fishtail, and Jack's Reef Pentagonal forms. There was a general lack of features or evidence of intra-site variability in this area, despite the wide range of projectile points representing long-term seasonal use of the site. Thus the two sites differ considerably even though close in proximity, with one focussing on the initial procurement of locally available quartz during the Late to Terminal Archaic period, while the other exhibits a focus on maintaining hunting equipment during a longer time frame. The two sites contain a moderate density of material and features with the capacity to add new information regarding quartz reduction strategies and continuity of settlement behavior through time.

A concrete and iron hoist tower placed directly above one of the mine shaft entrances

A "pepperbox" revolver

Proposed settlement pattern for the Troutbrook Valley area. Satellite task sites surround a base where lithic procurement and habitation camp sites were occupied on a seasonal basis.

While the effects of plowing distorted the relationship between surface distributions of artifacts and the subsurface sites they represent, a surface collection aided in the distribution of systematic subsurface shovel tests of a Phase I survey. Historic sites recorded during the Phase I survey include a tobacco barn and material associated with small commercial and residential structures of the late 18th through early 20th Centuries. All were found in highly disturbed contexts and dismissed from further evaluation.

While found scattered throughout the property at the surface, subsurface testing during the Phase I survey revealed three concentrated areas of prehistoric material. Phase II intensive testing of the southwest and eastern loci revealed a moderate density of material in relatively disturbed contexts. The western locus, however, revealed high densities of lithic material within a site area measuring five acres. While the material in the plowzone was out of context, Phase II shovel tests and excavation units revealed "in situ" deposits beneath the plowzone including an abundance of features within a core two-acre area. These features included traces of a hearth, a storage pit with burnt nut fragments, and various post-molds representing habitation structures, all visible beneath an interface between the plowzone and subsoil revealing parallel plow scars.

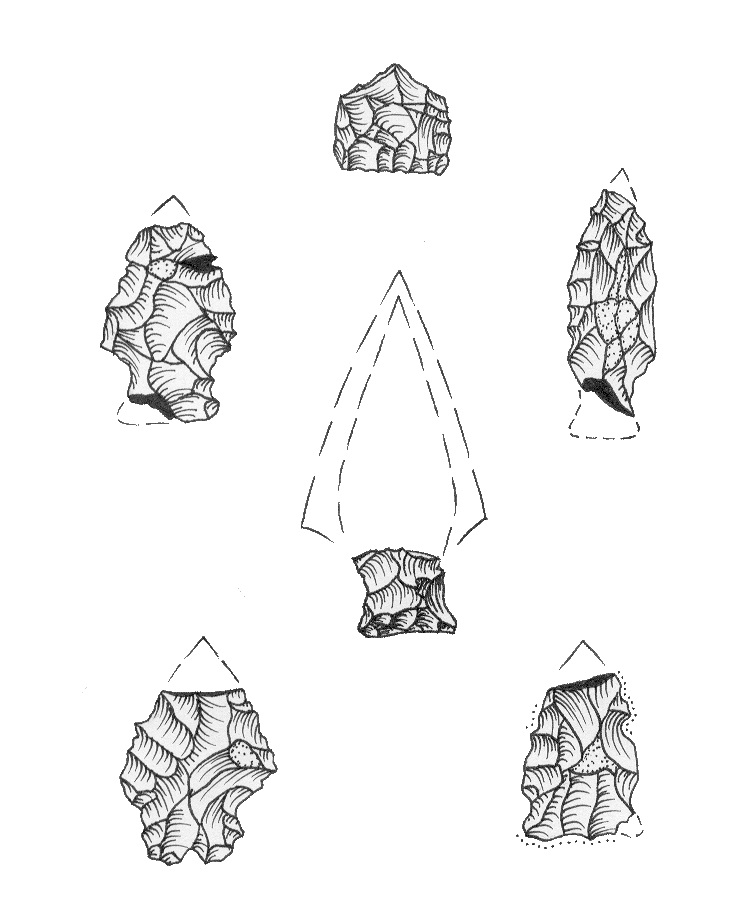

A radiocarbon date was attained through a charcoal sample from the hearth, generating a date of 4,460+70 B.P. or the early part of the Late Archaic period as confirmed by projectile points including Brewerton and Beekman types. Chert cores were also recovered, a rarity for the region as most of this material was traded into the area by neighboring exchanges of blanks and preforms rather than long forays or importation in bulk. Finally, the distribution of recorded post-molds indicate overlapping structures and thus repeated episodes of habitation and a settlement system in which seasonal movement took place. The site is tucked against a hill slope to the west, thus possibly representing use during winter when this landform would have offered considerable protection against prevailing winds from the northwest.

While the project property revealed a high density of cultural resources, ACS was able to minimize the extent to which the client was bound to consider aspects of cultural resource conservation through extensive phases of testing. The core area of the Larson Site easily qualified for the National Register of Historic Places with respect to the potential ability to add new and important information to the archaeological record. This project demonstrates the importance of finding a balance between community development and the need to conserve cultural resources.

Examples of lithic projectile points (upper row) and knives (lower row) recovered from the Larson Site. Most of the projectile points date to the Late Archaic period (ca. 5,000 to 4,000 years ago). The knives are less regular in shape, with dotted lines indicating visible use-wear along the lateral edges. A modern steel arrowhead found at the site is included for scale and comparative purposes.

Recording Impacted Cultural Resources: Groton - New London Airport

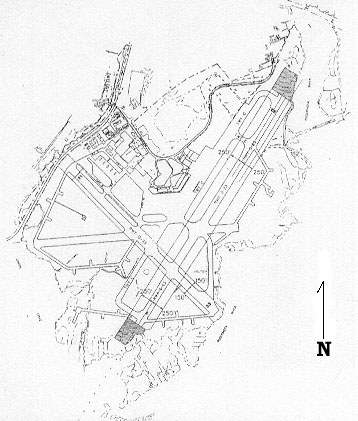

Under the auspices of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the Connecticut Department of Transportation (ConnDOT), ACS conducted a Phase II intensive archaeological survey of a prehistoric site identified at the Groton - New London Airport in Groton, Connecticut. The site dates to the Late Archaic period (ca. 5,000 to 3,000 years ago), representing a seasonally occupied coastal camp site.

The Groton - New London Airport lies on the west bank of the Poquonnock River that drains into the Long Island Sound within one-half mile to the south. ACS conducted a Phase I reconnaissance survey at each end of the main runway as part of a safety area improvement project, resulting in the confirmation of a previously recorded prehistoric site at the southern end. Bordering on a tidal inlet, the airport occupies an ideal setting for the presence of prehistoric sites, consisting of a nearly level surface supported by a well drained soil overlying a deposit of stratified glacial meltwater deposits. The tidal flats of the lower Poquonnock would have provided for an abundance of seasonally available anadromous fish and shellfish.

While the Late Archaic site revealed some disturbed contexts, much of the site is preserved and required a more intensive Phase II survey to establish its potential significance. The site partially extends into the wetlands that border the Poquonnock, indicating that it was likely occupied when sea levels were lower. Intensive testing at the site has revealed a moderate density of mostly quartz debitage, as well as several percussed lithic tools and projectile points of the Small-Stemmed tradition (e.g. Squibnocket, Lamoka). The lack of substantial features or broad diversity of material types at the site, however, is indicative of a limited range of functions which likely focussed on the short-term procurement and processing of estuarine resources.

Tracking Historic Structure Relocation through Time: Thomas Scranton House

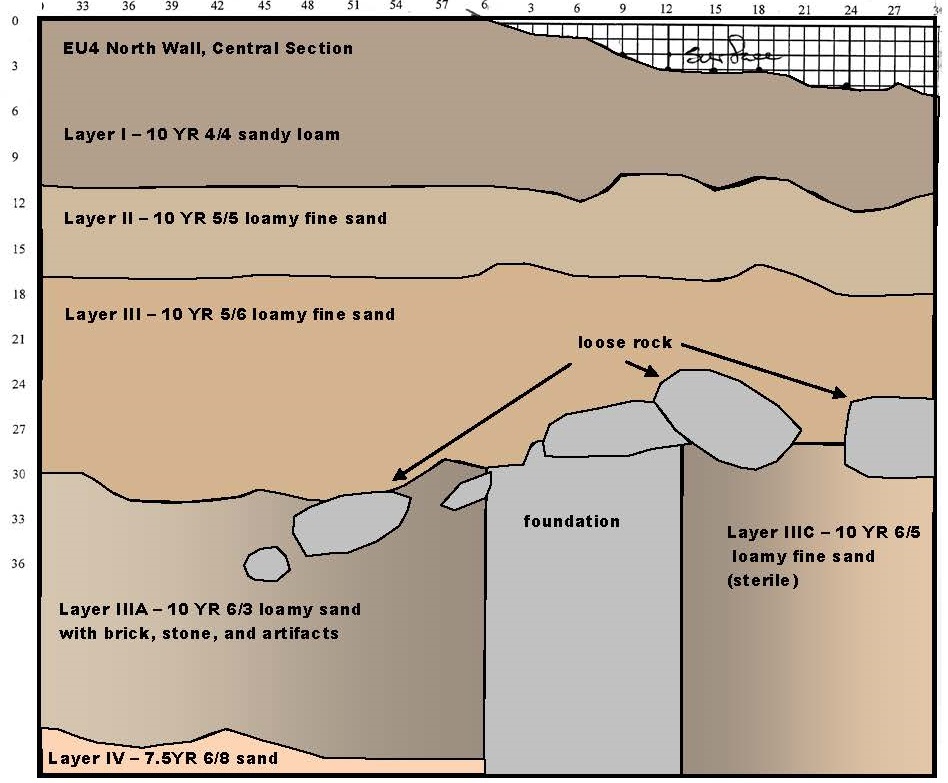

EU 4 revealed a stone foundation, with Layer III bearing three distinct facies, including a pale brown loamy sand in the western part of the unit rich in brick, stone, and artifacts; a dark yellowish brown loamy sand in the vicinity of the foundation wall; and a sterile light yellowish brown loamy fine sand mostly devoid of artifacts.

A Phase II intensive archaeological survey conducted at the Thomas Scranton House site in Madison, Connecticut revealed that the structure had undergone both relocation and renovations over time. ACS was able to provide sufficient structural documentation and delineation of significant portions of associated archaeological remains at the site to facilitate a proposed conversion of the historic structure into a community savings bank.

The Thomas Scranton House is located on a small lot measuring just over one-half acre on Route 1 at its intersection with Route 79 in Madison. A review of historic maps and land records revealed that the house was once part of a much larger eight-acre parcel, and that the original course of Route 79 was once to the west of the project property and adjacent parcel before being moved just east of the project property by the early 20th Century.

On the west side of the property lies the Deacon John Grave house that is the oldest surviving structure in Madison. The Scranton House appears as a Greek Revival structure with a recorded construction date between 1841 and 1850, although an architectural analysis of the structure, particularly its chimneys and fireplaces, reveals it to have been converted from a Colonial Cape style structure that was built between 1775 and 1786.

A Phase I reconnaissance survey of the project property revealed a surprising low density of historic artifacts in the direct vicinity of the house. More intensive Phase II intensive archaeological testing revealed a much higher density of historic artifacts as well as structural features to the east of the house and in close proximity to the road. This suggests that the house had been moved to its current location, possibly related to house renovations in the mid-19th Century.

The project property had a further complicating interpretive element in that there was a partial grave stone found embedded within the base of a large oak tree in the rear yard of the property, as well as a partial headstone from 1862 found in the basement of the house. Concerns were alleviated when testing revealed no grave feature associated with the stone embedded in the tree, with both gravestones likely recovered from graves at local cemeteries that were either vandalized or in disrepair, as was common practice for the area.

Projectile points from one locus indicate a long, albeit intermittent use of the site.

East view of the former gravestone embedded within the base of the copper beech tree behind the Thomas Scranton House (MHS 2011). The stone is no longer present, although remnants of the marble stone are present at the bottom of the remaining depression. A shovel test placed directly in front of the stone did not reveal traces of a grave feature.

While a Phase I archaeological reconnaissance survey is designed to merely document the presence of any prehistoric or historic sites in a project area that is slated for some form of development, the Phase II intensive archaeological survey is designed to document the context, integrity, and significance of each site. Context refers to the environmental setting of each site, including a more precise definition of site boundaries in horizontal and vertical space, and its depositional or stratigraphic disposition. It also refers to the functional and chronological nature of each site as determined by an analysis of artifacts, features, and structures. Integrity refers to the preservation state of each site, including disruptions to the stratigraphy, features, and/or depositional setting of artifacts by any natural or cultural forces.

A determination of significance for a site is based on guidelines set forth by the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, in the National Register Bulletin 16A (pages 35-51). These guidelines consist of criteria for determining the eligibility of a site's nomination to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), and broadly relate to its demonstrated "association with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history, association with the lives of persons significant in our past, embodiment of the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction, or its potential to yield information important in prehistory or history." The last criterion is the one most applicable to the majority of archaeological sites eligible for the register, and relates to potentially valuable or unique cultural information as determined in the Phase II survey.

Inclusion of a site into the NRHP ultimately results in the preservation or protection of significant cultural resources. Alternative recommendations for each site investigated during a Phase II survey may include "no threat to significant resources" in the event that a site is deemed to not be significant, in situ preservation by avoidance or project alteration, site acquisition with preservation restrictions, site preservation by inclusion in open space or limited-use areas, minimization of effect through engineering or construction method changes, site documentation and subsequent burial, and/or data recovery. The Phase III mitigation or data recovery programs are generally the last phase in the cultural resource management sequence of archaeological investigations, and are generally reserved for those cases where a significant site can not be reasonably avoided or preserved by the proposed development.

It should be noted that the majority of sites evaluated during a Phase II survey do not require Phase III mitigation given the alternatives listed above. Many of the sites evaluated during Phase II surveys were initially identified through Phase I surveys where a significant stratification of subsurface testing occurred in order to maximize the efficiency of the survey and minimize the cost to the client. The list above provides examples of Phase II intensive archaeological surveys performed by ACS, particularly those which have yielded an array of cultural resources and site data that have helped to document patterns of past cultural systems.

Phase II Intensive Archaeological Survey

The Poquonnock inlet was so rich in marine life that the property was also used during the historic era for the production of fish oil. The Morgan family operated an oil works at a fish house used to boil menhaden in large cauldrons, with the oil used for early industrial applications such as leather tanning, paint thinning, and machinery lubrication, and the remains dried and pulverized to make fertilizer. The historic fish oil works was likely located just outside the project area and thus not addressed with respect to conservation efforts, while the Phase II survey of the prehistoric site resulted in a recommendation of no further conservation efforts based on the degree of disturbance from prior landscaping efforts and a lack of material breadth or substantive features which could shed further light on prehistoric cultural adaptations. ACS has effectively prepared expert testimony for public hearings where local citizens have initiated numerous lines of attack against environmental compliance issues regarding this project.

Prehistoric Structural Remains and Features: The Larson Farm

The quartz cores are attributed to the Terminal Archaic period (ca. 3,700 to 2,700 years ago) and show a variety of reduction strategies which were necessary given the difficulty of working quartz as a lithic raw material

.

The most dramatic evidence of mining activity on the project property consists of cavernous subterranean shafts and tunnels which dot the landscape. These features typically occur where prominent bedrock outcrops reveal magnetite rich veins and deposits in formations targeted by the iron industry. The property also boasts equally prominent industrial features from the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, such as a ~60-foot concrete and iron hoist tower placed directly above one of the mine shaft entrances, and several other traces of concrete hoist platforms used to support machinery that extracted ore. Because of building hazards posed by the instability of the larger subterranean features and structural remains, the shaft and tower areas were avoided by the pending development, thus not a concern for Phase II testing.

The Sterling Forest section of southeast New York contains many traces of historic mining efforts. ACS conducted a Phase II intensive archaeological survey along sections of a historic road occupied by a mining community from the early 19th through early 20th Centuries. The project property exhibits multiple types of cultural resources related to the iron-mining industry of the region, including landscape features, industrial facilities, and traces of community dwellings.

Historic Mining District: Sterling Forest

ACS worked with project architects and engineers to ensure the conservation of critical cultural resources in light of the proposed development, which included moving the structure once again to its current location, as well as the construction of new septic fields and parking areas. Recommendations for the project included retaining one of three original fireplaces of the structure, moving the primary septic field away from the original house site to the other side of the structure, and capping the original house site with fill to a certain depth beneath the new parking lot.

The Phase II intensive archaeological survey evalutes the eligibility of sites for listing with the National Register of Historic Places. More intensive subsurface testing and larger excavation units allow for a detailed documentation of site characteristics, including site boundaries, chronology, functional setting, and integrity. These characteristics are used to determine site significance and guidance for recommending further possible conservation requirements.

The Phase II Process

ACS conducted an archaeological survey on a property consisting of an open field which had been plowed for 200 years as part of the Larson Farm in New Milford, Connecticut. The project area contains three historic sites as well as an abundance of prehistoric material and features such as structural post-molds, hearths, and storage pits from nearly 5,000 years ago.