One test adjacent to the house also produced a quartz Levanna projectile point typically found in Late Woodland sites (ca.1,000 to 350 years ago). The crudely formed point may date to the early part of the Contact period when the Whitfields purportedly engaged the services of local tribe members to assist in the construction of the house. It remains undetermined in the archaeological record whether the aboriginal materials and other structural features recorded to date are contemporaneous with the earliest Euroamerican occupation of the site. The Whitfield Site, however, provides the exciting possibility of documenting Native American and Euroamerican interactions in an agrarian, Contact-period setting.

ACS conducted an archaeological survey of a property in an area historically known as "Squabble Hole" in Ansonia, Connecticut. This area supported one of the first Euroamerican settlements on the outskirts of the New Haven Colony in the middle of the 17th Century. Unlike other early historic settlements of the region, Squabble Hole was located at a relatively great distance from the nearest major water source, and instead concentrated on a series of prominent hill ridges for protection against perceived threats from Native American tribes of the area.

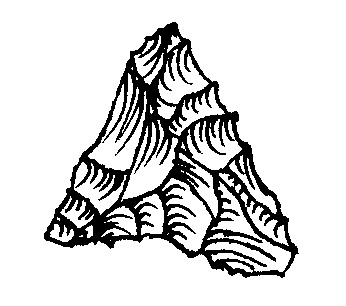

Four sites were identified on the property, including two prehistoric and two historic occupations. The first prehistoric site revealed evidence of food preparation, including deer bone processed for marrow extraction, a quartz knife, and a resharpening flake. The site lies near a marshy plain that was converted into a reservoir in the 19th Century. The second prehistoric site produced a Brewerton side-notched projectile point of the Late Archaic period (ca. 5,000 to 4,000 years ago). Most of the other artifacts from the second site represent the early part of the lithic reduction stream, including primary elements and flakes from quartz cobbles. The site lies near the confluence of two small intermittent streams which feed the reservoir and contain glacially transported cobbles that served as a source for lithic raw materials procured and processed at the site. Both sites suggest task-specific activities or short-term, seasonally restricted habitation.

Brewerton projectile point from the Late Archaic period (ca. 5,000 to 4,000 years ago)

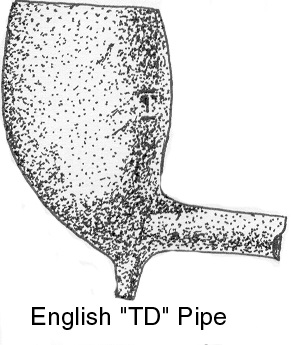

Kaolin clay 'TD' pipe bowl from the mid 19th Century

Prehistoric and Historic Coastal Occupations: Riverview Estates Subdivision

Earlier occupants of the Rogers Site, based on relative preservation states, predominantly relied upon Mya arenaria (soft shell clam) during a cooler environmental phase, while later occupants mostly relied upon the warmer adapted Argopectan irradians (Atlantic bay scallop). Evidence for mass shellfish procurement included a high density of dispersed shell remains as well as refuse pits containing large quantities of stacked scallop shell halves. This site was important, not only in demonstrating its potential for revealing changing ecological conditions and resource procurement strategies, but for its potential in showing latent aboriginal cultural adaptations that were severely altered or eradicated elsewhere during the Contact period.

Mercenaria mercenaria - the northern quahog. This species was a common food source consumed by coastal Native American groups. The shell was also used for the production of wampum, or purple and white shell beads that were exchanged with other inland Native American groups.

ACS conducted an intensive locational (Phase I) survey at the Valentine Site in Ashland, Massachusetts. The site is in the vicinity of a known Contact period burial ground that was impacted by road construction, although a variety of intact features from the 18th and 19th centuries remain at the site.

The Valentine site in Ashland includes a late 18th Century house and associated barn at the base of Magunco Hill. Magunco Hill is believed to be the site of Magunkaquag, which was the last of the seven “Praying Indian Towns” established by John Eliot in 1659. Remains of an associated burial ground were revealed during nearby road and house construction, thus the research design constructed by ACS called for a high density of shovel tests completely saturating the project property which was proposed to be used for a multi-family housing development.

There were no human remains or traces of burials revealed during the survey, although the yard surrounding the existing house revealed numerous traces of historic subsurface features and structural remains, including a possible privy, an outbuilding, post molds from historic fencing, and features related to house renovations over time. Recovered artifacts include wrought, cut, and wire nails; window glass; redware, creamware, pearlware, whiteware, and yellowware ceramic fragments; coal and slag; domestic mammal bone; shell; and personal items such as kaolin clay pipe fragments, an 18th Century brass button back, and late historic materials such as a clay pigeon fragment and a 1951 Roosevelt dime.

The first historic site identified on the property included cellar-holes from two residential structures, as well as the remains of a small outbuilding. Through historic maps and land records, it was determined that the site belonged to the Coe family during the late 18th through late 19th Centuries. Diagnostic materials were mostly limited to ceramic artifacts confirming the date range of occupation. The second site included a foundation of a smaller residential structure and a well. Historic sources indicate this latter location to have been occupied by the Coleman family from the early 19th through early 20th Centuries, as confirmed by a variety of diagnostic household ceramics. Foundations from both sites were made from locally available schists and gneisses which outcrop in the area. These historic occupations were associated with an agrarian use of the landscape, historically referenced as "orchards" or "farms" in local land records.

During a Phase I archaeological reconnaissance survey on the property of the early 19th Century Solomon Rogers House in Waterford, Connecticut, ACS located and identified a Late Woodland to Contact period open habitation site. The site lies on the east side of Niantic Bay in an area known to have been inhabited by aboriginal populations until the 18th Century. ACS was able to demonstrate that changing ecological conditions contributed to the shifting distribution of shellfish species collected during the occupation of this site.

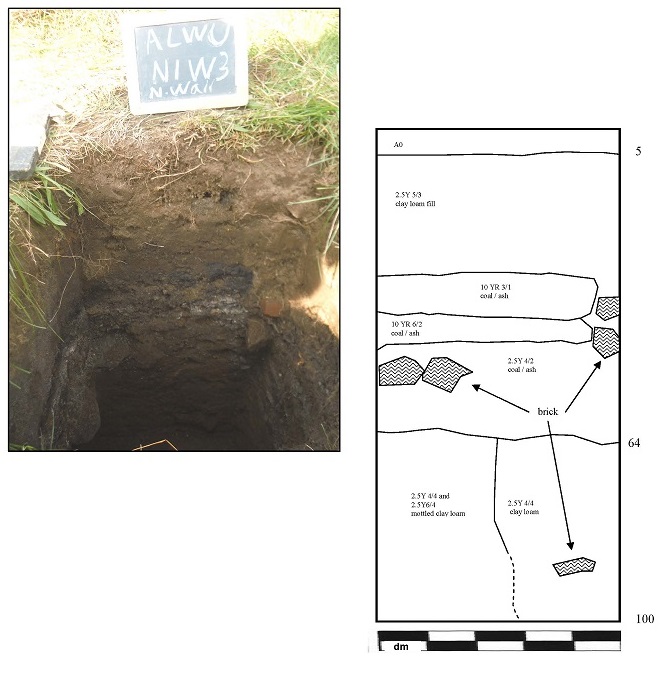

Left-Photograph; Right- Schematic profile of test N1-W3, west wall. This is possibly a privy feature with fill layers of clay loam and coal/ash overlying deeper clay loam layers.

Background research indicated that the Whitfield House was built around 1639, possibly with the help of local Native American inhabitants who were thought to have assisted in the transport of fieldstone from a local quarry for the construction of the house. Prior archaeological excavations on the grounds revealed numerous aboriginal lithic artifacts as well as the remains of a temporary or seasonal structure occupied by Native Americans, or possibly the Whitfield family until the stone structure was built.

.

The Phase I archaeological reconnaissance survey is designed to identify the existence of any prehistoric or historic archaeological resources within a project area. The reconnaissance survey typically involves background research, a pedestrian surface survey, an efficient subsurface testing strategy, analysis of recovered materials, and an interpretive report stating the results of research and testing. The report also contains professional recommendations regarding the disposition and suggested future conservation requirements of any cultural resources identified on the property.

The multi-component nature of the property reveals interesting changes with respect to land-use. While the small drainage basin and hilly terrain was limited to short-term hunting and gathering tasks during the prehistoric era, it was targeted by early Euroamerican settlers seeking to expand the settlement of the New Haven Colony. The choice of this area was recognized as a trade-off between limited agricultural potential and enhanced safety offered by the protective hill ridge setting. Agriculture on the property was largely abandoned by the late 19th Century as railroads and population expansion provided more efficient supplies of agricultural products from outside the region to major market centers in the Northeast.

.

Identifying Historic Features and Artifacts: The Valentine Site

The review agency for this project determined that the Valentine site was sufficiently documented during the Phase I survey that no further archaeological conservation efforts were required, and accepted developer plans to incorporate the existing historic house into the proposed development.

Prehistoric Camp Sites and Historic Agriculture: "Squabble Hole"

The Phase I Process

The National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) of 1966 reflected the broad-scale recognition of a need to protect cultural resources, defining historic preservation as "the protection, rehabilitation, restoration and reconstruction of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects significant in American history, architecture, archaeology or culture." Section 106 of the act requires all federal agencies to take into account the effect of any federal development project on such cultural resources which may be eligible for inclusion into the National Register of Historic Places (NHRP). Section 106 also authorizes a review process created by the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation as detailed in 36 CFR 800, by which qualified professionals evaluate the potential for properties to contain significant cultural resources and report such findings to a designated independent review agency, often the relevant State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) as established in Section 101 of the NHPA. The NHPA paved the way for a series of other federal, state, and municipal regulations which are tailored to address the need for heightened cultural resource conservation efforts.

While federal, state, and municipal agencies have internal mechanisms for mandating cultural resource studies in association with public development projects, private entities such as development corporations are typically notified of such a need by a relevant government agency only after requesting permits to proceed with a particular project. The development corporation is then required to perform the cultural resource study in advance of any major developments associated with a project, a logistical issue which frequently disrupts project scheduling if the requirement is not anticipated well in advance. Many companies are only now becoming aware of the greater complexities of project planning due to increased governmental regulations concerning cultural resources as well as a host of other environmental issues. There is a greater recognition in recent years, therefore, of the advantages found through advanced planning which incorporates "due diligence" studies ahead of such requirements.

The review agency, under which the regulatory domain of a development project lies, will typically expect a phased approach to the evaluation of cultural resources. The Phase I archaeological reconnaissance survey is designed to merely identify the existence of any prehistoric or historic archaeological resources within a project area. The reconnaissance survey, therefore, typically involves preliminary background research, a pedestrian surface survey, an efficient subsurface testing strategy, analysis of recovered materials, and an interpretive report stating the results of research and testing. The report also contains professional recommendations regarding the disposition and suggested future conservation requirements of any cultural resources identified on the property, which may include no further conservation efforts based on a lack of sites or poor preservation, a more intensive Phase II archaeological study of identified sites to evaluate their potential eligibility for inclusion into the NRHP, or some other mechanism designed to protect sites without further evaluation such as conservation easements or alternative design planning. The client or development corporation will typically be able to choose from alternative recommendations as ultimately approved by the review agency.

It should be noted that more than half of all Phase I surveys fail to reveal potentially significant cultural resources warranting further conservation efforts. The list above provides an example of Phase I archaeological reconnaissance surveys performed by ACS, particularly those properties which have yielded an array of cultural resources and site data revealing patterns of past cultural systems.

ACS had the privilege of conducting an archaeological survey on the grounds of the oldest house in Connecticut and the oldest stone house in New England. The site is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, with the house slated for a variety of improvements. The house was built under the direction of Henry Whitfield, a practicing reverend from England who also served as one of the founders of Guilford, Connecticut.

Field testing around the perimeter of the stone house revealed a mix of mid 18th through mid 20th Century artifacts. The materials were predominantly structural in nature, including slate roofing tile fragments, mortar, highly patinated window glass, and a variety of cut and wire nails. The majority of tests also revealed a builder's trench with a general lack of stratigraphy above a sterile substratum of glacial outwash sediments. The builder's trench features date to the 1868 reconstruction of the house which included a re-tiling of the roof and a re-mortaring of the stone walls below the surface, a conclusion supported by the chronological assessment of artifacts as well as the recovered mortar fragments which lack the yellow clay and crushed shell used in the original construction of the house according to historic accounts. The artifact assemblage also included a moderate density of household debris such as ceramics, glassware, domestic animal bone, shell, and a number of personal items reflecting an intermittent use of the house by tenant farmers for the bulk of its recorded history.

Phase I Archaeological Reconnaissance Survey

Oldest Stone House in New England: Henry Whitfield Museum