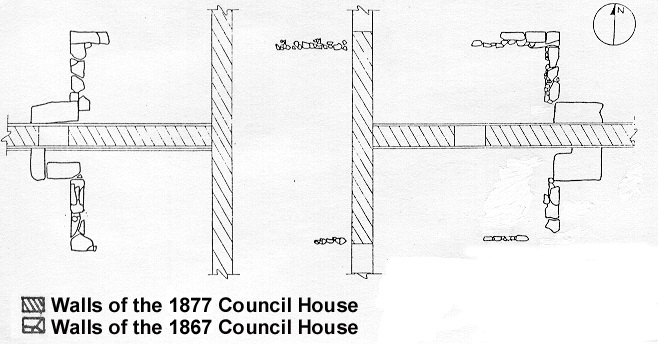

Plan drawing of the original Creek Council House foundation recorded beneath the floor of the existing Council House.

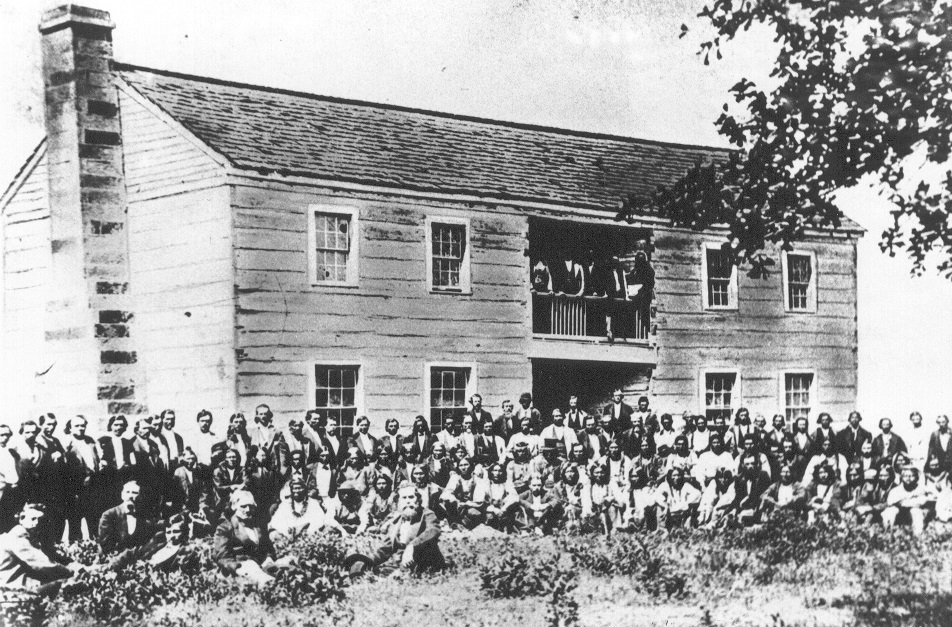

The original Creek Council House built in 1867

The second Creek Council House built in 1877

The council house represents efforts by the Creek Nation to maintain cultural and political autonomy in the face of severe adversities, including the removals of the early 19th Century which brought many of the Creeks to Oklahoma. As a place of communal gathering, the council grounds and the house can be viewed as part of a continuum of evolving Creek structures originating in pre-contact ceremonial plazas. Symmetric architectural layouts reflect duality in totem spirituality, aspects of which are bound by the mutual dependency in forces of nature and humanity. As a seat of government, the council house also incorporated aspects of Euroamerican culture, with a gold-plated eagle at the top of the cupola, and a political structure which shared many qualities with the federal government of the United States. The Creek Council houses thus display aspects of cultural continuity and change reflecting the efforts of a proud people to perpetuate their cultural heritage. Recommendations were submitted to preserve the original foundation and to conserve numerous materials associated with the construction and use of both buildings.

Native American Studies

ACS specializes in both prehistoric and historic archaeological surveys, often involving research of Native American lifeways. Southern New England is original home to many Native American groups that still maintain a strong cultural presence, while the Native American studies of ACS have also been conducted in Oklahoma where many of the nation's tribes were historically relocated. ACS incorporates archaeological evidence, ethnohistoric literature, and current traditional knowledge into its studies of Native American culture.

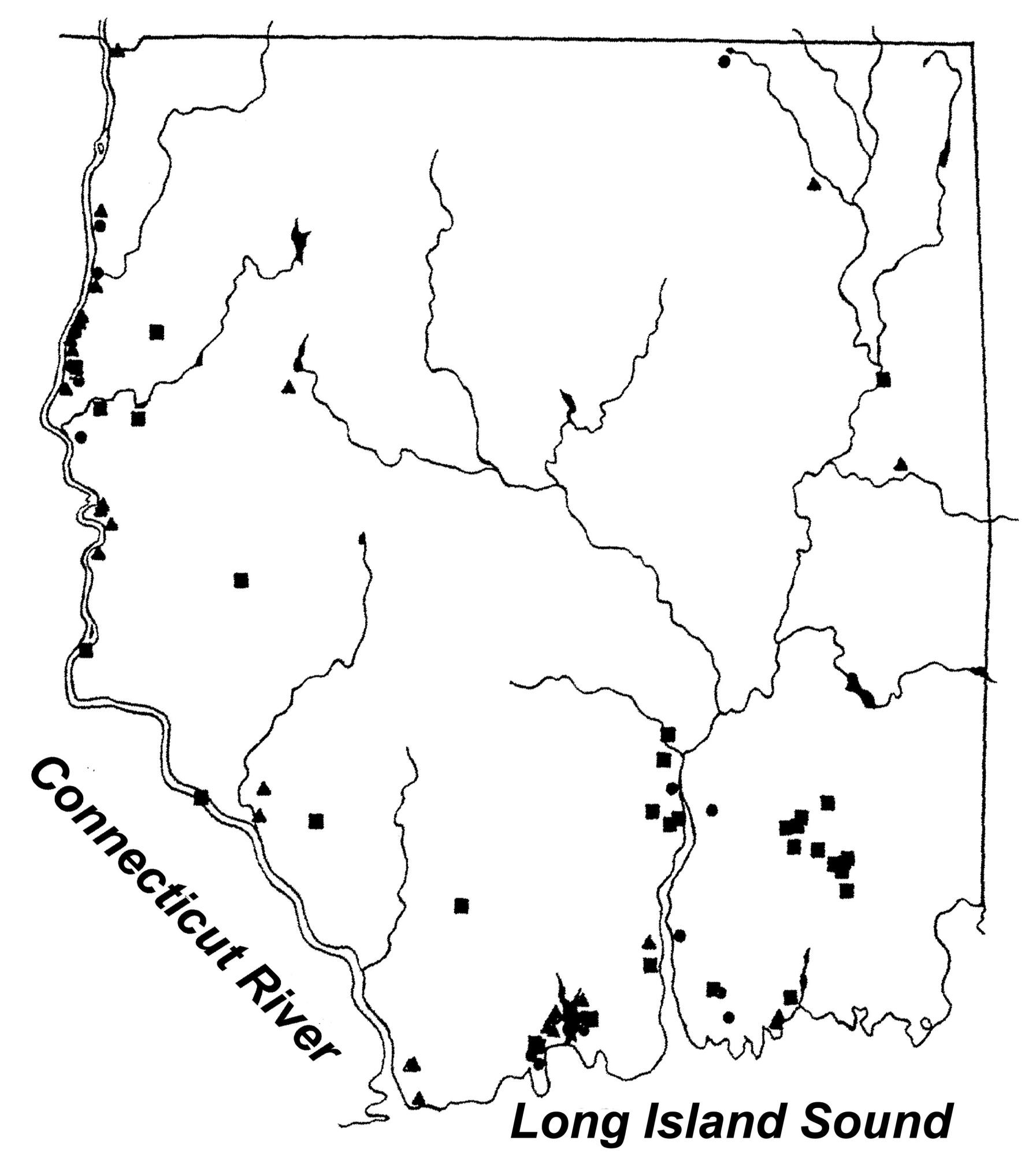

ACS conducted a research survey of Native American burials and cemeteries for the Connecticut Historical Commission. The project was designed to identify and evaluate sites and remains as they pertain to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). The project also revealed significant patterns of cultural behavior and change in mortuary practices which led to new interpretations of cultural adaptations in Connecticut prehistory. This highly sensitive research project required a confidential treatment of information from many sources, including Native American tribes, state site files, academic and professional archaeologists, local historians, private collectors, and historic literature.

Late Archaic cremation sites were found to occur in formalized settings away from habitation sites, an indication of semi-sedentary settlement patterns for at least a portion of the population. The elaborate nature of cremation sites by the Terminal Archaic suggests that the representatives of the Susquehanna Tradition had some control over restricted and critical resources. These resources included transportation routes, as well as steatite which was traded throughout the Northeast for the production of ceremonial objects and portable containers. The widespread development of ceramics during the Early Woodland period led to the decline of steatite as a rare and valuable resource, along with an associated decline of ceremonialism.

Skeletal remains which were partially preserved by copper compounds from funerary objects in Early Woodland sites indicate a 2,500-year limit for skeletal preservation in the region and that non-elite Narrow Point burials of the Late and Terminal Archaic are merely missing due to preservation factors. Late Woodland burials are represented by primary inhumations which are generally flexed, often oriented to the southwest as the legendary source of corn and direction of the Spirit Land, without durable funerary objects, and scattered in habitation settings. These burial conditions suggest an egalitarian setting for the Late Woodland despite agricultural resource intensification, which in turn supports the contention that agriculture never led to large economic surpluses or centralized control over critical resources in the region.

Distribution of documented Native American burial sites and historic cemeteries in eastern Connecticut. Prehistoric burial locations designated by triangles, historic cemeteries designated by squares, chronologically undetermined burial sites designated by circles.

Contact period burials more consistently express a southwest orientation and ceremonial character despite the disruption to aboriginal adaptations following the Euroamerican invasion. When these adaptations became impossible during the 18th Century, Christianity was more readily accepted by Native Americans, as indicated by epitaphs on headstones and east-west burial orientations. Burials were clustered, but now in marginal settings as Native Americans were effectively divested of prime agricultural land. The obfuscation of steatite during the Early Woodland and the disruption to settlement patterns during the Contact period were associated with latent forms of ceremonial mortuary practices, indicating that ideological structures were more resistant to change than many economic aspects of Native American adaptations.

The directors of ACS were engaged by the City of Okmulgee, Oklahoma, in cooperation with the Creek Indian Memorial Association, to monitor disturbance to the grounds of the Creek Council House during its restoration. The original Creek Council House of 1867 was destroyed by fire and replaced by the present stone structure in 1877. Archaeological monitoring led to the identification and mapping of the foundation for the original council house which lay directly beneath the center of the present structure.

There is a growing awareness of the conflict between Native American tribes and the scientific community regarding the goals and efforts of archaeology. While archaeological research attempts to reconstruct past cultural behavior through the analysis of material remains, Native American traditionalists widely hold that knowledge of the past comes from the body of lore which is transferred from generation to generation within a tribe.

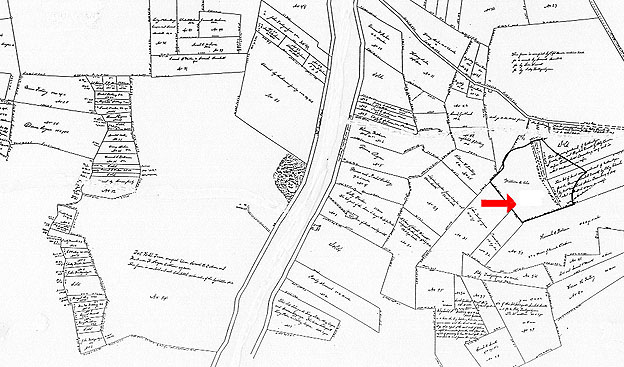

An 1860 map of the reduced land holdings of the Mohegans (red arrow shows project location).

Native American groups also view the landscape as sacred, particularly with respect to burial grounds, while archaeologists tend to view burial sites as rich resources offering a wealth and variety of information not easily attained from other site types. Despite these fundamental discrepancies in goals and priorities, there are increasing efforts on the part of both communities to find common ground on which to promote the conservation of sites deemed valuable in either world view.

Construction Monitoring: Creek Council House

ACS was approached by the Mohegan Tribe of Uncasville, Connecticut, in order to conduct an archaeological survey of a portion of Fort Shantok State Park. As part of the original territory of the Mohegans and a recent land settlement between the Mohegans and the federal government, the park was transferred to the tribe. During the Phase I survey, ACS confirmed the presence of two historic sites which had been identified during a previous field school. The sites included traces of a 19th Century barn, as well as a fieldstone foundation dating to the late 18th and early 19th Century. Materials from tests in the vicinity of the barn were limited to a kaolin clay pipe stem and several cut nail fragments, while those of the cellar-hole included hand- wrought nails, household ceramics, and domestic mammal bone suggesting a residential occupation about 200 years ago. Occupation and use of the property occurred during a time of considerable change for the tribe, as Euroamerican encroachments on tribal lands and the subsequent illegal sale of land by tribal overseers resulted in the drastic reduction of tribal territory and the ability for individuals to maintain aboriginal lifeways.

The Mohegans ultimately decided to not develop the land in deference to the historic sites which may offer significant new information regarding past changes in cultural and historic processes. While ACS offered a recommendation to limit preservation to the eight-acre core area containing the two sites, the tribe opted to preserve the entire property. ACS welcomed the monitoring of the survey by the Narragansett Tribal Historic Preservation Office which acted as review agency for the project. This project serves to reinforce the notion that there lies a balance between Native American tribal and archaeological concerns which can be adequately realized through coordinated efforts and a recognition of common ground in practice if not principle.

The Mohegans: Fort Shantok State Park at Mohegan

Native American Burials and Cemeteries in Eastern Connecticut